Graphic Design Pros And Cons

Even if you don't know much about graphic design, you can probably throw out a few cocktail-party-worthy truisms: "Comic Sans is just the worst typeface ever." That statement is irrefutable, right? As unassailable as grass being green, Shakespeare was a genius, and Tina Fey is way funnier than Seth MacFarlane. If you want to come off as a typography dilettante, you might make some seemingly inoffensive remark like, "Well, you can't go wrong with Helvetica." And if Craig Ward overheard you, he'd most likely shudder and take a subtle step toward the door. It's hackneyed statements like these that he tries to dismantle in his pocket-size Popular Lies About Graphic Design .

According to Ward, a New York–based British designer, Comic Sans "is the typographic equivalent of an innocent man on death row." Sure, it's ugly, he admits, but there are plenty of other bad handwriting fonts that don't stir up nearly as much unfair bile and vitriol. And as far as Helvetica goes, it's hardly the typographic corollary of the perfect black dress, suitable for any occasion. It may be "as ubiquitous a typeface as has ever existed," but don't mistake ubiquity for neutrality; Helvetica, in fact, is an "authoritative typeface with a distinct tone of voice." If you're looking for vanilla, you'd be well advised to look around for another font.

Don't feel bad if you've adopted some arguments Ward might find specious; even professional designers lean on well-worn rules and generalities to help create guidelines, and others will argue against them. You, like Mies van der Rohe and Dieter Rams, may subscribe to the philosophy of "less is more." In Popular Lies, Milton Glaser says that maxim is patently false. Ward says that the book is meant to encourage designers to experiment, "examining other possibilities when it may be easier to side with something tried and tested."

Here are a some of the choice gems, from Ward and some of his famous-designer friends in response to the question: What's the biggest lie you've ever been told about design?

1. Longer deadlines will lead to better work.

—Craig Ward

My experience may be unique. But for my money, you rarely need more than a few weeks for most still image projects. Obviously, if you're attempting something more ambitious, or time related, then you may need longer, but, really, three or four rounds of amends over the course of a couple of weeks is usually ample. Much more and you can end up wasting your time chasing unworkable ideas or losing focus, much less and you may feel under too much pressure to deliver and that, in itself can be equally stifling.

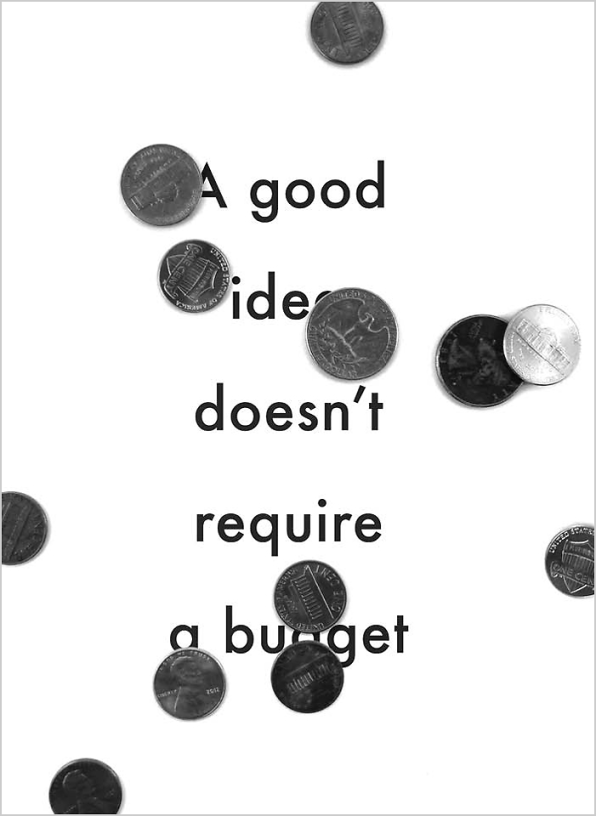

2. There's no budget, but it's a great opportunity.

–Craig Ward

And that would be an opportunity for what exactly?

If you go your entire career without receiving this kind of a proposition, you're doing either extremely well or extremely badly depending on your mindset. The idea that it's okay for you to spend days of your time creating work for world-renowned clients who aren't paying you a decent wage is pretty shameful–yet often unavoidable. Unless you set your stall out very early on and stick to your guns.

5. Stay Small.

–Willy Wong

"Stay small" was a piece of advice I heard quite often when I began my career. Smaller studios and a small circle of clients–I was told–meant more control and thus (work of a) higher quality. In fact, go solo if you could.

Nowadays, I find that nothing happens in a silo and that everything is connected. If you've got sharp kerning skills, good intentions, and the ingenuity to spin gold out of thin air, why not add solid management skills to your belt and be able to kill it at scale? The world seems to need designers more than ever. What's wrong with being part of a group, playing in a team, forming a league, building a community. Not everyone has the capacity to manage process, budgets, expectations, or personalities, but if you got 'em, why not go for it? Balls out!

6. "We don't have any money."

—Craig Redman

They probably won't. Sorry.

Remember that even these so-called lies should be taken with a grain of salt; design is subjective, and you're entitled to your own bloody opinions. As Ward writes in his introduction, "This is not a book full of facts. Nor is it a book full of advice. It's a book full of opinions, and confusion between those three is how a lot of these problems begin." In other words, don't feel you need to take other people's espoused opinions as facts.

Buy the book here for $11.

Graphic Design Pros And Cons

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/1672032/7-of-the-biggest-lies-in-graphic-design-2

Posted by: cooktheartumety.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Graphic Design Pros And Cons"

Post a Comment